Yesterday I went to look for Devon. I’m working on the chapter ‘M5 Escapes’, and wanted to check out the region’s ‘prettiest village’ which has a popular castle, a ‘Simon’ church (England’s Thousand Best Churches by Simon Jenkins has been my touring bible for years), walk part of the Exe Valley Way, eat lunch in a pub for which I’d read a rave review, and visit Devon’s first Quaker Meeting House which The Shell Guide (1975) calls ‘a treasure’.

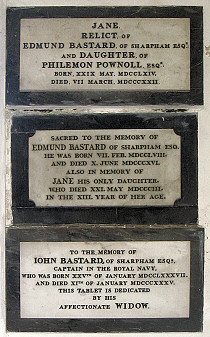

First to the Quaker Meeting House. The address was ‘Spicelands’ which sounded more like a shelf in the supermarket than a village – and which I couldn’t see on the map – so I found the post code on the internet. Lydia, my SatNav, loves a challenge and was almost bouncing with enjoyment as she took us up ever narrower roads ‘til proudly saying ‘You have reached your destination’. And, after several stints of driving backwards and forwards, reversing haphazardly into muddy gateways, there it was. A woman holding a basket of washing looked at us in dismay and said it was only open on Sundays for a service and one day a year for the general public. But she kindly showed us its simple interior and indicated where the graveyard was. It’s a very chocolatey graveyard full of Frys, and Cadburys, and Rowntrees; all Quakers.

A baby bank vole, we decided

The real excitement here was what we found in the garden. A tiny ball of fur, smaller than a golf ball, on the lawn with trembling whiskers, closed eyes and little pressed-in ears. Not a mouse. Not a shrew, we collectively decided, and not well. But as we watched, it started to recover, wash its face, and look around. A few minutes later it was scampering to the safety of the rose bed. Our British mammals book suggests that it was a baby bank vole. It was one of the cutest little animals I’ve seen for ages. The question is, what had happened to shock it into immobility? I think maybe a bird of prey had grabbed it and dropped it as we rounded the corner.

The Meeting House won’t go into Go Slow Devon.

Lydia next took us to Cruwys Morchard — don’t these Devon villages have wonderful names? But in this case I found myself disagreeing with Simon. The church is quite dull, and the revolving lychgate that he mentions turns out to be painted mental-hospital brown, and be utterly unremarkable. But then I’ve discovered the unremarked and unpraised revolving lychgate at Rousdon, near my home town of Seaton, which is beautifully carved and has a ‘coffin slab’ for resting the coffin on while opening the gate. I feel smug about that find, specially since Hoskins, the Devon authority (1954), said the church ‘has nothing to commend it’.

But I digress. Cruwys Morchard won’t go into Go Slow Devon; it’s not worth the diversion.

Then to Butterleigh for lunch. A niceish village and a good pub with a lovely garden. But worth the diversion? No. Bickleigh, a few miles away, was the main focus of the day. It’s in all the guidebooks, described as ‘a very pretty village of thatched houses’, ‘picturesque’, ‘a well-known beauty spot’ and ‘suffering from coach party fatigue’.

The main draw was the castle. Well, the village is indeed quite pretty, though the thatched houses are spread out up steep hills which must challenge the coach parties, and the church was more interesting for the very jolly women decorating it for a wedding than for an exceptional interior. The castle was closed. For good. The owners have found that being a venue for weddings is more profitable.

We asked a woman to point out the start of the Exe Valley Way. ‘It’s very muddy’ she said, looking doubtfully at our trainers. She was right. And so many walkers have tried to avoid the mud by deviating from the path that… well, you guessed it, we took the wrong path, nearly fell in the Exe, and decided to come back another day properly equipped. But I found some chanterelle mushrooms which I ate for supper. Delicious!

Bickleigh and the Exe Valley Way will go in the book, but only after a return visit.

Hazel teapot topiary in Culmstock

So to the last village, Culmstock. There’s a tree growing out of the church tower which I wanted to photograph. Otherwise I didn’t think there was much there. It turned out to be the best visit of the day. We passed a garden with a hazel bush clipped into the shape of a teapot, a bridge over the delightful River Culm, and some attractive but unpretentious houses. Teapots made me think of tea, and the pub was closed, so we headed for The Strand Stores which had a welcoming sign saying ‘Shop Now Open. Café’ and a blackboard showing their specialities: Sheppys cider, Bottle Green, Fresh cheeses. Inside you could see that the goods had been selected to reflect what people in the village actually want to buy, rather than what the shop owner thinks they want to buy. There were tins of organic tomatoes and chick peas, gluten- and wheat-free brown flour, and ethical plain white flour. Our coffee and cake were properly prepared and of high quality.

The former post office was a victim of the post-office closures two years ago, much to the dismay of the villagers, and was reopened in its new guise early this year. It’s a perfect example of village initiative and how to turn a disaster into a triumph. One of the local vets who was shopping in the store when we were there said that everyone who lives or works in the village does their best to support it. ‘We bring reps here for breakfast meetings,’ she said ‘and I come here almost every day for something’.

The feeling of serving and being served by the community was strengthened by the rows of home-made jam on the shelves. ‘Sometimes local people will buy up the tail end of our fruit, when it’s starting to go soft’, said the assistant, ‘and then sell us the jam they’ve made.’

This is just how a village shop should be; Culmstock, and The Strand Stores, will definitely go in the book. Oh, and the church tower was covered in scaffolding. I only hope they’re not removing the tree! Something else I have to find out.