I promised Exmoor on my last blog. Yes, I’ve been there (several times) but there’s a bit of detective work still to be done, so back again to Devon villages to teasing out truths about churches, and the people who are commemorated there.

St Paul in stained glass at Doddiscombsleigh church

Let’s start with Doddiscombsleigh (sometimes just pronouncing these Devon villages is a challenge!). I went there because it has the best medieval stained glass windows in the county, but then my attention was caught by an explanatory sheet by a Dr Tisdall. He pointed out that a medieval face carved at the top of one of the stone capitals is unusual. It has funny pointy ears, unusual foliage, and there’s something strange about the mouth. Now Dr Tisdall is a medical doctor with a passion for the unusual in Devon churches, so he has teased out the (probable) truth here. This carving is at the west end of the church which is often called The Devil’s End (indeed, some old churches have a little opening through which the devil can escape during services), and he has a hare lip.

The "Devil's bite" carving

As a young doctor studying children’s diseases, Dr Tisdall came across the expression ‘devil’s bite’ to describe a hare lip. And the foliage isn’t the usual rose leaves, it’s Succisa pratensis, or Devil’s bit scabious. So there we have it. A medieval carver portrayed the Devil in an instantly recognisable form – to the villagers of his day – but for us it takes the detective work of a knowledgeable enthusiast to get to the truth.

x

x

Carved snail

Moving on to Ashprington, near the River Dart, to a church which goes unremarked in other guidebooks. But it’s always worth popping into a village church – you never know what you’ll find. And indeed, there was a lovely carved pulpit with a cute little snail attacking the vine leaves (well, Sharpham vineyard is just down the road and they probably have the same problem) but what attracted my attention – how could I avoid it? – was a memorial stone to three generations of Bastards. Not a common surname these days so I did a bit of research. The character who emerged was Captain Philemon Pownall.

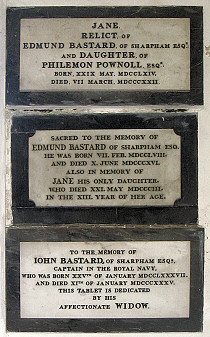

Three generations of Bastards

This captain made a fortune at sea. The first references I could find were that he received ‘prize money’ for capturing a ship full of treasure. That seemed like simple piracy to me, but my fellow researcher, Janice, dug deeper and found that he literally struck gold. Only three months after war broke out with Spain in 1762 he was captaining a warship that captured the Spanish man-of-war Hermione. What they didn’t know was that she was no simple warship: she had set sail from Lima before the outbreak of war and was carrying bags of dollars, gold coin, ingots of gold, silver and tin.

So ‘prize money’ was, in those days, the government reward for the prize of a captured ship: in Pownall’s case, £64,872. Seldom has a lottery winner put their money to better use.

Capt Philemon Pownall by Joshua Reynolds, 1762

Pownall and his fellow captain Herbert Sawyer, had earlier been courting the two daughters of a merchant from Exeter, who had refused their suits because their financial status didn’t meet his standards. Now they could marry their sweethearts.

Pownall continued to spend his money lavishly. He commissioned the making of a delicate miniature gold gazebo, called ‘Love’s Triumph’ for his wife Jane, had his portrait painted in full naval uniform by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and commenced the building of his manor at Sharpham. The estate has a river frontage of nearly three miles, with gardens designed by Capability Brown. It was his daughter, also Jane, who made the unfortunate marriage to Edmund Bastard. They had no sons.

So there are two things I didn’t know before I started doing this book.